Il cinema di esplorazione: la scuola di Cooper eSchoedsack/ Cooper-Schoedsack

and Friends

un programma a cura di / a programme curated by Kevin Brownlow

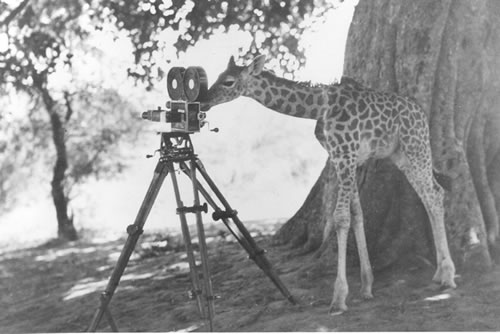

Stampede, 1928

(Kevin Brownlow

Collection)

The motto of Cooper-Schoedsack

Productions: "The Three Ds — Distance, Difficulty, Danger"

Filmare i fatti della vita è la più nobile istanza

della cinematografia. Il desiderio di informare ed educare, ma anche di

intrattenere, è la massima aspirazione di un cineasta. Eppure quanti

sono i film di questo tipo non liquidabili con la formula che invariabilmente

associa l’aggettivo "noioso" al sostantivo "documentario"?

Fu per descrivere l’opera di Robert Flaherty che John Grierson coniò

tale sostantivo. Ed è a Flaherty che Cooper e Schoedsack si ispirarono.

Ma i documentari s’erano sempre fatti, sin dalla nascita del cinema,

specie in Francia, dove Charles Pathé riteneva suo dovere istruire

il pubblico. Tuttavia è con Flaherty che l’elemento umano

assume importanza. Cooper e Schoedsack elaborarono questo concetto aggiungendovi

alcuni dei tratti tipici del film a soggetto, consapevoli com’erano

che per rendere vivo un film lo dovevano manipolare e che il pubblico

andava stupito. Essi esordirono con documentari "puri" come

Ra-Mu e Grass per approdare a film drammatici girati in

esterni come Chang e coronare infine la propria carriera con

King Kong, parodia della figura del cineasta esploratore. Il loro

lavoro ispirò altri autori, la cui produzione è inclusa

in questa retrospettiva.

Merian C. Cooper ed Ernest

B. Schoedsack sono due degli uomini più straordinari che io

abbia mai conosciuto. Basso, esuberante e dinamico, Cooper era riuscito

a fare tante di quelle cose nella vita da riempire un’intera serie

di libri d’avventure, eppure continuava a vantarsi come un ragazzino.

Schoedsack, alto e bello come Gary Cooper, aveva trasformato le sue

avventure in aneddoti autocritici. I due erano molto uniti, anche se Monte

Schoedsack tendeva a prendere in giro Coop in modo impietoso. Uno dei

miei ricordi più belli risale a quando li riunii dopo un lungo

periodo di separazione e mi fecero morire dal ridere con le loro battute

di spirito.

Nel copione di King Kong, Ruth Rose si era richiamata a Cooper

per il personaggio di Denham (Robert Armstrong) e a Schoedsack per Driscoll

(Bruce Cabot). La storia è quella di un regista di documentari

che va a girare un film su un’isola misteriosa portandosi dietro

— per avere qualche chance in più al botteghino — anche

una ragazza (Fay Wray). Ad un certo punto, durante il viaggio in nave,

lui le fa un provino.

"Denham: ‘Bene. Adesso provo con un filtro.’ Ann: ‘Fate

sempre voi le riprese?’ Denham: Sì, da quando sono stato in

Africa. Avrei potuto realizzare un magnifico film sulla carica di un rinoceronte,

ma l’operatore si spaventò. Che idiota! Io ero lì con

il fucile, ma evidentemente lui non credeva che io avrei beccato il rinoceronte

prima che gli piombasse addosso. Da allora ho chiuso con gli operatori.

Mi arrangio da solo.’ Stacco sul ponte. Il capitano Englehorn (Frank

Reicher) e Driscoll si chinano a guardare Denham ed Ann. Driscoll: "Comandante,

pensate che sia un pazzo?’ Englehorn: ‘No, solo un entusiasta.’"

— Kevin Brownlow

The factual film is the

cinema’s most noble endeavour. The desire to inform and to educate,

as well as to entertain, is the highest aspiration of the filmmaker. Yet

how seldom do such films rise above the level of the dull — and a

word that invariably follows — documentary?

The word "documentary" was coined by John Grierson to describe

Robert Flaherty’s work. And Flaherty served as an inspiration for

Cooper and Schoedsack. Documentaries had been made from the birth of the

cinema, especially in France, where Charles Pathé felt a responsibility

to educate his audiences. Until Flaherty, however, few documentaries had

any kind of human element. Cooper and Schoedsack took this idea and added

some of the strengths of the feature film. They knew that to make films

vivid they had to be manipulated and that the audience had to be astonished.

They began with "pure" documentaries — Ra-Mu and

Grass — and graduated to dramatic films made on location —

Chang — climaxing their careers with King Kong, which

parodied the role of the expedition filmmaker. They inspired others, some

of whose work we will include in this season.

Merian C. Cooper and Ernest

B. Schoedsack were two of the most extraordinary men I ever met. Cooper,

short, exuberant, and dynamic, achieved enough in his life to fill a series

of adventure stories. Schoedsack, as tall and as handsome as Gary Cooper,

converted his adventures into self-deprecating anecdotes. The two men

were very fond of each other, even though Monte Schoedsack tended to tease

Coop unmercifully. One of my most delightful memories was bringing the

two men together after a long interval and being helpless with laughter

at their repartee.

In her script for King Kong, Ruth Rose wrote Cooper into the character

of Denham (Robert Armstrong) and Schoedsack into Driscoll (Bruce Cabot).

The story concerns a documentary filmmaker and his journey to a mysterious

island. He takes a young girl (Fay Wray) along to give his film some chance

at the box office. Aboard ship he makes a test.

"Denham: ‘That was fine. I’m going to try a filter on this

one.’ Ann: ‘Do you always take the pictures yourself? Denham:

‘Ever since a trip I made to Africa. I’d have got a swell picture

of a charging rhino, but the cameraman got scared. The darned fool. I

was right there with a rifle. Seemed he didn’t trust me to get the

rhino before it got him. I haven’t fooled with cameramen since. Do

the trick myself.’ Cut to bridge. Captain Englehorn (Frank Reicher)

and Driscoll leaning over, watching Denham and Ann. Driscoll: ‘Think

he’s crazy, skipper?’ Englehorn: ‘Just enthusiastic.’"

— Kevin Brownlow

In her script for King Kong, Ruth Rose wrote Cooper into the

character of Denham (Robert Armstrong) and Schoedsack into Driscoll (Bruce

Cabot). The story concerns a documentary filmmaker and his journey to

a mysterious island. He takes a young girl (Fay Wray) along to give his

film some chance at the box office. Aboard ship he makes a test.

DENHAM: That was fine. I’m going to try a filter on this one.

ANN: Do you always take the pictures yourself?

DENHAM: Ever since a trip I made to Africa. I’d have got a swell

picture of a charging rhino, but the cameraman got scared. The darned

fool. I was right there with a rifle. Seemed he didn’t trust me to

get the rhino before it got him. I haven’t fooled with cameramen

since. Do the trick myself.

Cut to bridge. Captain Englehorn (Frank Reicher) and Driscoll leaning

over, watching Denham and Ann.

DRISCOLL: Think he’s crazy, skipper?

ENGLEHORN: Just enthusiastic.

COOPER & SCHOEDSACK

Merian Coldwell Cooper

Nato in Florida nel 1893, era figlio avvocato. A sei anni ricevette

in dono il libro di Paul Du Chaillu Explorations and Adventures in

Equatorial Africa, la cui descrizione di come le scimmie terrorizzassero

i villaggi della giungla e di come una di esse rapisse una donna urlante

è all’origine di King Kong. Merian decise che, come

Du Chaillu, avrebbe fatto l’esploratore. Nel 1911 entrò ad

Annapolis come cadetto, ma era "troppo vivace e fu colto in

flagrante troppe volte", così abbandonò l’accademia

ed andò nella marina mercantile. Dopo aver lavorato in un quotidiano,

si unì alla Guardia Nazionale della Georgia pensando che lo avrebbero

mandato in Europa: invece lo spedirono al seguito di Pershing sul confine

messicano. Durante la prima guerra mondiale prese parte come aviatore

alla battaglia di Saint-Mihiel. Abbattuto sulle Argonne, fu fatto prigioniero

dai tedeschi; dopo la guerra andò in Polonia con la American

Relief Association. I rifugiati russi lo convinsero che il comunismo era

una minaccia mondiale e nel 1919, quando l’Armata Rossa invase la

Polonia, egli fu uno dei fondatori della squadriglia anti-bolscevica Kos´ciuzsko,

composta da dieci aviatori americani. Fu di nuovo abbattuto, questa volta

dalla cavalleria di Budiennij, e fatto prigioniero dall’Armata Rossa.

Condannato a morte, riuscì a fuggire e fu decorato dal maresciallo

Pi´lsudski. Di ritorno negli Stati Uniti, divenne giornalista,

ma il suo desiderio di fare l’esploratore lo spinse ad accettare

di scrivere un libro sul giro del mondo del capitano Edward Salisbury.

Quando il cameraman ingaggiato da quest’ultimo diede forfait, Cooper

mandò un telegramma a Schoedsack e fu così che nacque il

celebre duo.

Dopo i film Grass, Chang e The Four Feathers (Le

quattro piume), Cooper tornò a occuparsi di aviazione, iniziando

nel contempo a buttar giù idee per King Kong. Nel 1931 si

unì alla RKO come assistente esecutivo di David O. Selznick, di

cui prese il posto all’uscita di Kong.

Durante la seconda guerra mondiale, Cooper fu il capo di stato maggiore

del generale Chennault in Cina, congedandosi con il grado di generale

di brigata. Nel 1947, con John Ford, fondò la Argosy Pictures,

che produsse classici quali She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (Icavalieri del

Nord Ovest) e The Searchers (Sentieri selvaggi). Nel 1949,

con Schoedsack, tentò di bissare il successo di Kong con

Mighty Joe Young (Il re dell’Africa). Nel 1952 entrambi

collaborarono con Lowell Thomas a This Is Cinerama. Nello stesso

anno Cooper ricevette un Oscar speciale "per le molte innovazioni

ed i contributi apportati all’arte cinematografica". Morì

nel 1973. — KB

Merian Coldwell Cooper was

born in Florida in 1893, the son of a lawyer. At the age of 6 he was given

Paul Du Chaillu’s Explorations and Adventures in Equatorial Africa,

finding the seeds of King Kong in the book’s account of apes

that terrorized jungle villages — including one that carried off

a screaming woman. He decided, like Du Chaillu, he would become an explorer.

In 1911, he entered Annapolis as a cadet, but was "too high-spirited

and got caught too many times", as he put it. He resigned and joined

the merchant marine. After working as a newspaperman, he joined the Georgia

National Guard, thinking he would be sent to Europe, but was sent instead

to Pershing’s army on the Mexican border. As an aviator in World

War I, he participated in the Battle of St. Mihiel. Shot down in flames

over the Argonne, he became a prisoner of the Germans. After the war,

he went to Poland with the American Relief Association. Russian refugees

convinced him that Communism was an international threat. When the Red

Army invaded Poland in 1919, Cooper helped to form the Kos´ciuzsko

Squadron, a group of ten American aviators, to fight the Bolsheviks. Again

he was shot down, this time by Budienny’s cavalry, and he became

a prisoner of the Red Army. Sentenced to death, he made an epic escape

and was decorated by Marshal Pi´lsudski.

Back in the United States, he became a newspaperman. But his ambition

to become an explorer caused him to sign on with Captain Edward Salisbury

to write a book about his round-the-world expedition. When the cameraman

quit, Cooper cabled Schoedsack, and the famous team was born. After their

films Grass, Chang, and The Four Feathers, Cooper

returned to aviation. But he began to sketch plans for King Kong,

and in 1931 joined RKO as an executive assistant to David O. Selznick,

whom he succeeded when Kong was released.

During World War II, Cooper served as Chief of Staff to General Chennault

in China, and retired with the rank of Brigadier General. In 1947, he

formed Argosy Pictures with John Ford, co-producing such classics as She

Wore a Yellow Ribbon and The Searchers. He and Schoedsack tried

to repeat the success of Kong with Mighty Joe Young (1949).

In 1952, both men worked with Lowell Thomas on This Is Cinerama.

That same year he received a special Academy Award "for his many

innovations and contributions to the art of motion pictures". Cooper

died in 1973. — KB

Ernest Beaumont Schoedsack

Nato nel 1893 a Council Bluffs, in Iowa, se ne andò da casa

a 12 anni. Nel 1914 si unì, in qualità di operatore, alla

Mack Sennett Keystone Company; durante la prima guerra mondiale fu in

Francia come operatore di guerra del Genio Collegamenti. Prese poi parte,

ufficialmente sempre come cameraman, ad una missione di soccorso della

Croce Rossa in Polonia, dove si prodigò a favore dei profughi.

L’incontro con Cooper avvenne alla stazione di Vienna: Schoedsack,

che indossava una lacera uniforme ed aveva con sé una spada della

marina, era stato appena rilasciato da una prigione tedesca. I due viaggiarono

insieme fino a Varsavia. Schoedsack documentò la guerra contro

i russi, poi prese parte alle operazioni internazionali di assistenza

in Medio Oriente e filmò la guerra greco-turca del 1921-22. La

sua attività a favore dei rifugiati fu riconosciuta anni dopo con

una medaglia al valore.

Su invito di Cooper, egli partecipò alla spedizione Salisbury e

dopo Grass sposò Ruth Rose, la futura sceneggiatrice di

King Kong. Nel 1931 lavorò in India a The Lives of a Bengal

Lancer (I lancieri del Bengala), che Lasky aveva progettato come una

speciale produzione Cooper-Schoedsack, ma essendo impegnato nel settore

dell’aviazione civile, Cooper dovette rinunciare al progetto. Schoedsack

effettuò numerose riprese che non furono mai usate se non in travelogues

o come materiale di repertorio in film quali The Last Outpost

(L’avamposto) del 1935. I continui rinvii nella lavorazione di

Bengal Lancer lo spinsero a lasciare la Paramount per unirsi a Cooper

alla RKO. Non seguì il montaggio di Kong per recarsi nel

deserto siriano a riprendere esterni per un film intitolato Arabia,

che non fu poi realizzato (questo materiale finì poi nel film di

Léonide Moguy Action in Arabia [La spia di Damasco] del

1943). Pur lavorando alle dipendenze di uno studio, Schoedsack non amava

Hollywood. Durante la seconda guerra mondiale andò in Inghilterra

per curare le riprese riguardanti la RAF per il film Eagle Squadron

(1942). Un incidente con una maschera ad ossigeno, occorsogli mentre

testava ad alta quota il suo equipaggiamento fotografico, gli lese gravemente

un occhio; nonostante le operazioni, venne perdendo gradualmente la vista

e alla fine dovette abbandonare il cinema. Per gli ultimi 35 anni della

sua vita fu praticamente cieco, ma continuò a lavorare, occupandosi

di registrazioni sonore. Con Ruth Rose assemblò, su incarico di

Cooper e Lowell Thomas, i materiali che costituivano il prologo storico

di This Is Cinerama. Morì nel 1979. — KB

Ernest Beaumont Schoedsack

was born in l893 in Council Bluffs, Iowa, and ran away from home at the

age of 12. He joined the Mack Sennett Keystone Company as a cameraman

in 1914 and in World War I was a combat cameraman with the Signal Corps

in France. Schoedsack joined a Red Cross relief mission in Poland, officially

as a cameraman, but he was able to provide help for refugees. He met Cooper

at the railway station in Vienna — Cooper had just been released

from the German prison and wore a battered uniform and carried a naval

sword — and they travelled to Warsaw together. Schoedsack filmed

the war against the Russians and then joined the Near East Relief and

filmed the Greco-Turkish war of 1921-22. His help for refugees was acknowledged

years later with a Distinguished Service Medal.

He joined Cooper on the Salisbury expedition, and after Grass Schoedsack

married Ruth Rose, who would write the script of King Kong. During

1931, he worked in India on The Lives of a Bengal Lancer, which

Lasky planned as a Cooper-Schoedsack special. But Cooper had to cry off,

as his airline interests were occupying his time. Schoedsack shot a great

deal of footage which was never used, except in travelogues and as stock

in films like The Last Outpost (1935). The interminable delays

over Bengal Lancer caused him to leave Paramount and join Cooper

at RKO. He missed the editing of Kong because he went to the Syrian

desert to film backgrounds for a film called Arabia, which was

never made. (Footage was later used in Léonide Moguy’s 1943

film Action in Arabia.) Schoedsack worked as a studio director,

but never liked Hollywood. During World War II, he travelled to England

and took charge of shooting the RAF material for Eagle Squadron

(1942). An accident with an oxygen mask while testing photographic equipment

at high altitude severely damaged his eye. Operations failed to help and

led to a gradual loss of sight, causing him to retire from pictures. He

was virtually blind for the last 35 years of his life, and he turned to

sound recording. Cooper and Lowell Thomas gave him and Ruth Rose the job

of assembling the film history footage that introduced This Is Cinerama.

Schoedsack died in 1979. — KB

RA-MU (US, 1924/1934)

Prod.: Captain Edward A. Salisbury; ph.: Ernest B. Schoedsack,

Merian C. Cooper; narr.: William Peck; dist./released: 3.8.1934;

versione riodtta in due rulli /2-reel extract, 35mm, c. 21’

(24 fps), sound-on-film, BFI/National Film and Television Archive.

Narrazione in inglese, senza didascalie / English narration, no intertitles.

L’uomo che portò al sodalizio professionale

di Cooper e Schoedsack fu il capitano Edward Salisbury, esploratore ed

esperto di film di spedizioni, che aveva incaricato Cooper di scrivere

il resoconto del suo viaggio attorno al globo. Egli aveva ingaggiato un

operatore americano, che però, quando la nave incappò in

un tifone, si scoraggiò talmente da abbandonare la spedizione a

Colombo. Fu così che Cooper si mise in contatto con Schoedsack

e lo fece venire a Gibuti. Quando Salisbury si ammalò, Cooper e

Schoedsack realizzarono il loro primo film insieme ad Addis Abeba, riprendendo

Ras Tafari, principe reggente dell’impero abissino (il futuro Hailé

Selassié, imperatore d’Etiopia), che aveva mobilitato per

la macchina da presa il suo esercito di 50.000 uomini.

La Wisdom II andò a cozzare contro uno scoglio e riportò

gravi danni; fu così ormeggiata a Savona, dove gli operai provocarono

un’esplosione di gas che avrebbe danneggiato tutto il materiale girato

da Schoedsack (eppure in Ra-Mu ce n’è ancora molto).

In viaggio per Parigi, Cooper e Schoedsack discussero il progetto di un

film imperniato sulla lotta dell’uomo contro la natura — non

un travelogue, ma la storia di un drammatico conflitto nello stile

di Robert Flaherty e di Nanook of the North (Nanuk l’eschimese).

Cooper, ritornato negli U.S.A. per reperire i fondi, ritrovò a

New York Marguerite Harrison, che aveva lavorato nello spionaggio americano

e gli aveva passato cibo e denaro a Mosca prima di essere anch’ella

imprigionata come spia. Fu lei ad aiutarlo con i finanziamenti, così

Cooper, con orrore di Schoedsack, la invitò ad accompagnarli nella

spedizione che avrebbe dato vita al film Grass.

Riedizione sonora di una versione muta, Captain Salisbury’s Ra-Mu

(1929) non cita né Schoedsack né Cooper nei titoli,

come del resto Gow the Headhunter (1933), che pure utilizza delle

loro riprese. Forse furono proprio Cooper e Schoedsack a volere così,

poiché si trattava di materiale che avevano girato all’inizio

della loro carriera mentre ora erano all’apice della fama. —

KB

The man who brought Cooper and Schoedsack together

professionally was Captain Edward Salisbury, an explorer and a veteran

of expedition films. Salisbury hired Cooper to write the book of his round-the-world

expedition. He also hired an American cameraman, but the ship ran into

a typhoon, which so demoralized the cameraman that he jumped ship at Colombo,

and Cooper contacted Schoedsack. He joined the expedition at Djibhouti,

and when Salisbury fell ill, Cooper and Schoedsack made their first film

together in Addis Ababa, photographing Ras Tafari, Prince Regent of the

Abyssinian Empire (later Haile Selassie, Emperor of Ethiopia), who assembled

his army of 50,000 for the camera.

The Wisdom II struck a rock and, seriously damaged, put into dry

dock at Savona, Italy. Workmen caused a gas explosion which supposedly

wrecked all the film Schoedsack had shot. (And yet Ra-Mu includes

much of it.)

As Cooper and Schoedsack set out for Paris they discussed plans for a

film about man’s struggle against nature, not a travelogue but a

story of dramatic conflict in the style of Robert Flaherty and Nanook

of the North. Cooper returned to the U.S. to find the finance, and

in New York was reunited with Marguerite Harrison, who had served in American

intelligence and had smuggled food and money to him in Moscow before she,

too, was jailed as a spy. She helped raised the money, and Cooper, to

Schoedsack’s horror, invited her to accompany them on the expedition

that became Grass.

This sound reissue of a silent version, Captain Salisbury’s Ra-Mu

(1929), fails to credit either Schoedsack or Cooper. Nor did his 1933

Gow the Headhunter, which also used Schoedsack and Cooper footage.

Perhaps this was at their instigation, for the material shot at the beginning

of their careers was appearing when their reputation was at its height.

— KB

GRASS: A NATION’S BATTLE FOR

LIFE (Famous Players-Lasky, US 1925)

Prod./dir.: Merian C. Cooper, Ernest B. Schoedsack; ph.: Ernest

B. Schoedsack; didascalie di/ ed./titles: Terry Ramsaye & Richard

Carver; partitura orig. / orig. music score: Hugo Riesenfeld &

Edward Kilenyi; cast: Marguerite Harrison, Merian C. Cooper, Ernest

B. Schoedsack, Haidar Khan (capo tribù /chief of Bakhtiari tribe),

Lufta (suo figlio /his son), i membri della tribù dei Bakhtiari

/people of the Bakhtiari tribe; dist.: Paramount Pictures;

released: 30.3.1925; 35mm, 5793 ft., 73’ (22 fps), The Museum

of Modern Art.

Didascalie in inglese / English intertitles.

I documentari americani ai giorni del muto erano spesso diretti a due

mercati, le sale cinematografiche ed il circuito delle conferenze. Marguerite

Harrison apparve in Grass per dimostrare, nelle conferenze di presentazione

del film ai circoli per signore, che aveva effettivamente partecipato

alla spedizione (scrisse anche un libro, There’s Always Tomorrow,

che contiene un resoconto del viaggio e una divertente descrizione di

Cooper e Schoedsack).

I due cineasti non avevano idea di dove andare o di che tipo di film realizzare:

tutto accadde per caso. Essi partirono per la Turchia, con l’intenzione

di attraversare l’Anatolia per giungere in Turkestan, ma i turchi

li scambiarono per spie inglesi e li trattennero per settimane. Quando

finalmente riuscirono ad entrare in Anatolia, Schoedsack effettuò

delle riprese di interesse turistico ancora presenti nel film.

Al momento dell’incontro con i Bakhtiari, la piccola spedizione aveva

finito quasi tutti i soldi e consumato parecchia pellicola; peraltro,

il suo arrivo coincise con l’inizio della migrazione annuale della

tribù. Il grande viaggio dei Bakhtiari cominciò il 17 aprile

1924, coinvolgendo, secondo quanto annotato nei diari di Cooper, almeno

50.000 persone e mezzo milione di animali.

Nessun cineasta potrebbe sperare in una scena più sbalorditiva

di quella dell’attraversamento del vasto fiume Karun, con le sue

gelide acque rigonfie di neve sciolta e piene di gorghi, correnti contrarie,

rapide. "Non credevo che fosse possibile farcela," scrisse Cooper.

"Sarebbe venuto l’infarto al comandante di qualsiasi esercito."

Le tribù ce la fecero con l’ausilio di zattere di pelli di

capra. "Per cinque giorni Schoedsack ed io, mentre correvamo di qua

e di là con le cineprese, assistemmo alla più grande ed

ininterrotta sequenza d’azione che si sia mai vista."

A quell’epica avventura seguirono ostacoli ancor più terribili:

quasi 500 metri di roccia a strapiombo da superare solo per trovarsi di

fronte il massiccio montuoso dello Zardeh Kuh. Quando giunsero finalmente

in cima — e furono i primi stranieri — e cominciarono la discesa,

Schoedsack non aveva neanche 30 metri di pellicola per mettere insieme

un finale.

Sia per lui che per Cooper era ovvio che il lavoro non era finito. Bisognava

tornare sul posto l’anno successivo per seguire la nuova migrazione

e filmare la famiglia di Haidar Khan, il capo tribù. Questa famiglia

avrebbe avuto un ruolo di primo piano durante il viaggio di ritorno. Si

sarebbe così realizzato un vero e proprio lungometraggio dove ci

sarebbe stato ampio spazio per l’uomo, l’azione e lo spettacolo

con un inizio, un centro e una fine, gli ingredienti essenziali di una

produzione Cooper-Schoedsack. Quello che avevano adesso era solo un mezzo

film. A Parigi vendettero fotografie per pagare il montaggio e Cooper

scrisse per alcune riviste. Schoedsack partecipò ad una spedizione

alle Galapagos, dove incontrò la sua futura moglie, Ruth Rose.

Cooper accompagnò Grass in un ciclo di conferenze e fu così

che Jesse Lasky lo vide e si offrì di distribuirlo. Dopodiché

alla Paramount si accorsero che tutto quel materiale girato non conteneva

neanche un’inquadratura degli uomini che lo avevano realizzato. Arrivarono

allora dal guardaroba due camicie sportive e le inquadrature iniziali

del film furono girate a New York, nei pressi di una roccia dietro gli

Astoria Studios della Paramount.

"Rimpiangerò finché campo di non essere tornato a completare

Grass. D’altra parte, se il film non fosse uscito, non avremmo

visto un soldo." — KB

American factual films in the silent days were often

prepared for two markets, the motion picture theatres and the lecture

circuit. Marguerite Harrison appeared in Grass to prove that she

had made the trek when she lectured with the film to ladies’ clubs.

(She wrote a book, There’s Always Tomorrow, which contains

an account of the expedition and an entertaining description of Cooper

and Schoedsack.)

The men had no idea where to go or what kind of film to make. It all developed

by accident. They set out for Turkey, intending to cross Anatolia to Turkestan.

The Turks thought they were British spies and wouldn’t let them in

for weeks. When they finally managed to penetrate Anatolia, Schoedsack

shot some travelogue footage, which is still in the picture.

By the time it encountered the Bakhtiari, the little expedition had spent

most of its money and had cut deeply into its film supply. But they arrived

just as the Bakhtiari were about to leave on their annual migration. The

Great Trek began on 17 April l924. Cooper’s diary records at least

50,000 people and half a million animals on the move.

No filmmaker could hope for a more astounding scene than the crossing

of the vast Karun River — icy cold, its waters swollen to a torrent

by melting snows, filled with whirlpools, cross-currents, and rapids.

"I was ready to say it can’t be done," wrote Cooper. "It

would have given any army commander heart failure." The tribes achieved

it with the aid of goatskin rafts. "For five days Schoedsack and

I, rushing about with the cameras, watched the greatest piece of continuous

action I have ever seen."

That epic adventure was followed by even more daunting obstacles: 1500

feet of sheer rock cliff, and when they had surmounted that, they were

faced with the massive mountain peak, Zardeh Kuh. When they finally crossed

the summit — the first foreigners ever to do so — and began

the descent, Schoedsack had only 80 feet of film left to contrive an ending.

The men acknowledged, however, that they had not finished. They needed

to return the following year to accompany the tribes on their next migration,

in order to film the family of Haidar Khan, the chief of the tribe. They

wanted to show that family in the foreground of the return journey. Thus

they hoped for a full-length feature picture, with a great deal of human

interest, plenty of action and spectacle, and the essential ingredients

of a Cooper-Schoedsack production — a beginning, a middle, and an

end. As it was, they felt they had just half a picture. In Paris, they

sold photographs to pay for the editing and Cooper wrote stories for magazines.

Schoedsack joined an expedition to the Galapagos, where he met his future

wife, Ruth Rose. Cooper subsequently lectured with Grass. Jesse

Lasky saw it and offered to release it. But then Paramount discovered

that in all the mass of footage there was no shot of the men who made

it. So they sent down to wardrobe for a couple of soft shirts, and the

shots that open the picture were taken by a rock behind Paramount’s

Astoria Studios in New York.

"To my dying day," said Cooper, "I regret that we did not

go back and complete Grass. But until we released it we couldn’t

get any money." — KB

Evento speciale / Special musical presentation

CHANG / CHANG: LA JUNGLA MISTERIOSA (Paramount Famous Lasky

Corp., US 1927)

Prod./Dir.: Ernest B. Schoedsack, Merian C. Cooper; ph.: Ernest

B. Schoedsack; titles: Achmed Abdullah; orig. music score:

Hugo Riesenfeld; cast: Kru Muang (il pioniere /the pioneer),

Chantui (sua moglie /his wife), Nah (il figlio /their son),

Laor Daroonnart (Ladah, la figlia /their Daughter), Bimbo (la

scimmia /the Monkey); New York premiere: 28.4.1927; lungh.or./orig.

length: 6536 ft.; 35mm, 6164 ft., 68’ (24 fps), Milestone Films

and Video, NJ.

Didascalie in inglese / English intertitles.

Nuovo accompagnamento musicale di / New

musical score by Philip Carli.

Chang non era un documentario più di quanto

non lo fosse King Kong. Fu concepito come un affascinante "dramma

naturale" che prendeva spunto dalla famiglia assente in Grass

per narrarne la lotta contro la giungla. Come esempio di cinema è

superbo, ben al di sopra della media dei documentari, ma, siccome non

costitutiva un esempio di vita vera ripresa senza manipolazioni, era difficile

da collocare ed ancor più difficile da approvare da parte dei puristi.

Cooper e Schoedsack si misero in viaggio senza avere né un copione

né un titolo. Avevano però il sostegno di Jesse Lasky ed

alcune idee di base su cosa filmare. Quando giunsero a Bangkok, capitale

del Siam (oggi Tailandia), iniziarono a cercare gli esterni: Schoedsack

esplorò l’Indocina laddove Cooper si dedicò al Siam

meridionale. Venne detto loro che in Siam non c’erano più

tigri, ma i missionari li indirizzarono verso la provincia di Nan: "L’inverno

scorso le tigri vi hanno ucciso diciannove persone." Senza i missionari,

spiegò Schoedsack, non avrebbero combinato nulla. "Ci trovarono

portatori ed interpreti, fecero per noi tutto il possibile. Certo erano

circondati da cristiani convertiti per un pugno di riso, ma erano brava

gente."

Misero a loro disposizione anche una casa abbandonata e li aiutarono a

scegliere fra la gente del posto gli interpreti del film. La madre, Chantui,

era la moglie di uno dei portatori; si credeva che il marito fosse un

carpentiere locale, ma di recente Serge Viallet ha scoperto che era in

realtà un insegnante cristiano ("Kru" significa proprio

"insegnante"). La ragazzina era sua figlia (e vive tuttora in

Tailandia). Il ragazzo indicato come Nah era suo fratello Sa-nga. C’era

anche il gibbone di Kru, Bimbo.

Cooper e Schoedsack ebbero modo di conoscere le tigri attraverso una dura

esperienza diretta. "I libri dicono che una tigre salta tre metri

e trentacinque al massimo", ha raccontato Schoedsack. "Così,

per la scena in cui la tigre balza sull’albero, ho sistemato la mia

piattaforma a quattro metri d’altezza, beh, sarà arrivata

a tre metri e ottanta."

Con Chang, Cooper e Schoedsack puntavano ad una forma di realismo

drammatico ottenuto osservando come le cose accadono e ricreandole a beneficio

della macchina da presa. Cooper separò un’elefantessa dal

suo piccolo, che legò ad una casa. Preparata la macchina da presa,

la madre venne lasciata libera. "Arrivò come un bolide,"

riferì Cooper. "Voleva liberare il suo piccolo; sapevo che

ci sarebbe riuscita, ma non pensavo che avrebbe buttato giù la

casa."

Uno dei metodi per cacciare gli elefanti fu suggerito dal Macbeth

(via The Covered Wagon [I pionieri]): i siamesi si nascosero dietro

a degli arbusti avanzando come la foresta di Birnam. Stando a Cooper,

i cacciatori di elefanti siamesi apprezzarono talmente questa tattica

che l’adottarono essi stessi, facendola così diventare autentica.

I sistemi realmente utilizzati per ottenere le stupefacenti scene con

gli animali sono rimasti un segreto che Cooper si è sempre ostinatamente

rifiutato di svelare, ammettendo solo di averli trovati in un libro del

XIX secolo.

Le principali sequenze con gli elefanti furono girate a Chumphon, nel

sud. Il re aveva una propria mandria che poteva calpestare impunemente

campi e villaggi. Ciò diede a Cooper l’idea per l’apice

drammatico di Chang, quando un branco di 300 elefanti distrugge

un villaggio. Venne scavata una fossa per la macchina da presa azionata

da Schoedsack, che intanto aveva preso la malaria. A Bangkok c’era

un americano che produceva un cinegiornale locale, e fu a lui che Cooper

e Schoedsack affidarono il prezioso negativo contenente la carica degli

elefanti. Di solito spedivano i negativi alla Paramount, ma prima di lasciare

il Siam volevano essere sicuri che la scena madre fosse a posto, e lo

sarebbe stata, se non avessero preso proprio tale precauzione. L’americano

rovinò i giornalieri e Schoedsack dovette rifotografare il negativo

fotogramma per fotogramma, con un lungo tempo di posa per ciascuno di

essi. Di qui l’effetto grana della sequenza, che fu comunque scelta

per essere proiettata in Magnascope, con conseguente amplificazione del

difetto, e che in seguito verrà riciclata in molti film, fra cui

quelli della serie di Tarzan. (Scene tratte da Chang, Grass

e The Four Feathers compaiono nel film del 1935 The Last Outpost

[L’avamposto], con Cary Grant e Claude Rains, per la regia di

Louis Gasnier e Charles Barton.)

Una sola unica ripresa fu fatta allo zoo del Central Park. La scimmia

che lanciava noci di cocco conto l’elefante non era venuta bene,

"Così andammo a tirare noci al docile e macilento elefante

del Central Park."

Un popolare romanziere dall’esotico nome di capitan Achmed Abdullah

fu ingaggiato per dare un tocco orientaleggiante alle didascalie, ma le

sue spiritosaggini sono un insulto al film (del resto, in Grass

neanche Terry Ramsaye aveva fatto molto di meglio). Eppure Cooper e Schoedsack

approvarono quei testi; e Cooper stesso aggiunse qualche didascalia. Se

lo stile fiorito del conferenziere vittoriano sopravvisse fino ai FitzPatrick

Travel Talks, il tono delle didascalie di Grass e Chang

sarebbe stato ripreso in decine di documentari americani fino True-Life

Adventures disneyane. Il film ebbe un successo enorme e per le sue

"qualità artistiche" fu anche candidato ad uno dei primi

Oscar (vinto però da Sunrise [Aurora]). Robert Flaherty

parlò di "trionfo della verità" (Ciné-Cinéa,

15 ottobre 1927, p. 23) e Rex Ingram ne scrisse in termini entusiastici

in uno speciale articolo per il Theatre Magazine (gennaio 1928,

p. 64). — KB

Chang was no more a documentary than King Kong.

It was conceived as a spellbinding "natural drama", utilizing

the central family missing from Grass and depicting that family’s

struggle against the jungle. As a piece of filmcraft, it is masterly and

stands far beyond the other documentaries in that regard. But since it

was not an unrehearsed record of real life, it was hard to categorize,

and harder still for purists to approve of.

No script existed — and no title — when the two men set off.

They had the support of Jesse Lasky and some firm ideas about what they

were going to shoot. When they arrived in Bangkok, the capital of Siam

(now Thailand), they set out on location trips, Schoedsack exploring Indo-China

while Cooper investigated lower Siam. They were told that tigers no longer

existed in Siam, but missionaries sent them to the Nan province: "Last

winter tigers killed nineteen people." Without the missionaries,

said Schoedsack, they would have achieved nothing. "They supplied

us with carriers and interpreters, and did everything for us. Of course

they were surrounded by rice Christians, but they were a good crowd."

The missionaries provided them with a deserted house and helped them find

local people to play in the film. The mother, Chantui, was the wife of

one of the carriers. The husband was said to be a local carpenter, but

Serge Viallet found out recently that he was a Christian teacher ("Kru"

means "teacher"). The small girl was his daughter (and still

lives in Thailand). The boy billed as Nah was her brother Sa-nga. And

there was Kru’s pet gibbon, Bimbo.

Cooper and Schoedsack gained their knowledge of tigers from harsh experience.

"The books tell you no tiger jumps over 11 feet high," said

Schoedsack. "So for the shot where the tiger leaps up the tree, I

built my platform at 13 feet. I think he jumped 12 and a half."

The approach for Chang was to achieve dramatic realism by observing

how things happened and causing them to happen again for the camera. Cooper

separated a mother elephant from her baby and tied the baby to a house.

When the camera was ready, the mother was set free. "She came like

a bat out of hell," said Cooper. "She just wanted to free her

baby, and there’s nothing staged about that. I knew she would get

the baby loose — but I didn’t know she was going to tear down

the house."

One method of hunting elephants came from Macbeth (via The

Covered Wagon): the Siamese concealed themselves behind bushes and

advanced like Birnam Wood. Cooper said the Siamese elephant hunters liked

the idea so well they adopted it, and it thus became authentic.

The actual methods used to obtain the startling animal scenes was a secret

Cooper steadfastly refused to divulge. He came upon it, he said, in a

book published in the 19th century.

The major sequences with the elephants were shot at Chumphon, in the south.

The King had his own private herd — it could trample fields and villages

with impunity. That was what gave Cooper the idea for the climax of Chang,

when a herd of 300 elephants destroys a village. A pit was dug for the

camera, and Schoedsack operated while suffering from malaria. An American

in Bangkok ran a local newsreel, and Cooper and Schoedsack entrusted him

with their precious negative of the stampede. Normally they shipped the

negative to Paramount, but before they left Siam they wanted to be sure

their big scene was all right. It would have been, had they not taken

this precaution. The newsreel man ruined the rushes. Schoedsack had to

step-print the negative, giving a long exposure to every frame. The final

result looks grainy. It was this sequence which was chosen to be projected

in Magnascope, making it look grainier still. It later cropped up as stock

footage in many films, including Tarzan pictures. (Chang,

Grass, and The Four Feathers all turned up as stock footage

in the 1935 film The Last Outpost, starring Cary Grant and Claude

Rains, directed by Louis Gasnier and Charles Barton.)

One shot, just one shot, was taken in Central Park Zoo. The monkey bouncing

cocoanuts on the elephant had not registered satisfactorily, "So

we went and bounced cocoanuts off the tame, mangy elephant they had in

Central Park."

A popular novelist with the picturesque name of Captain Achmed Abdullah

was hired to add an oriental flavour to the titles. His cute, wisecracking

titles are an affront to the picture. (Terry Ramsaye’s were not much

better on Grass.) Yet Cooper and Schoedsack passed them, and Cooper

wrote some of them himself. If the flowery style of the Victorian lecturer

survived into the era of the FitzPatrick Travel Talks, the comedy

titles of Grass and Chang would be perpetuated in scores

of American documentaries, including the Disney True-Life Adventure

films. The film was enormously successful, and it was nominated for "artistic

quality of production" for one of the first Academy Awards (it lost

to Sunrise). Robert Flaherty called it "a triumph of truth"

(Ciné-Cinéa, 15 October 1927, p.23), and Rex Ingram

raved over it in a special article for Theatre Magazine (January

1928, p.64). — KB

Alle Giornate

2003 Chang viene proposto con un accompagnamento musicale eseguito

da una piccola orchestra di sala paragonabile a quelle che negli anni

Venti si potevano trovare nei cinema di medie dimensioni in città

di medie dimensioni.

Il cue sheet compilato per Chang nel 1927 esiste tuttora e, per

ricrearne l'effetto, Philip Carli, nel preparare lo score per questa serata,

l'ha utilizzato il più possibile. Tuttavia non tutti i brani musicali

ivi suggeriti sono stati rintracciati. Probabilmente anche all'epoca il

direttore musicale di un cinema di medie dimensioni in una città

di medie dimensioni non disponeva di certi spartiti e pertanto sostituiva

un pezzo con un altro simile.

Quando il maestro Carli non è riuscito a trovare valide alternative,

ha colmato le lacune con proprie composizioni originali. Un servizio questo

che, presumibilmente, non veniva fornito dal direttore d'orchestra di

un cinema di medie dimensioni in una città di medie dimensioni.

Per fortuna, le Giornate possono vantare l'apporto di musicisti di calibro

ben superiore a quelli che si esibivano nel nostro ipotetico cinema di

medie dimensioni e confidiamo pertanto che i risultati del loro lavoro

possano soddisfare il pubblico dello Zancanaro. - Alice Carli

The musical accompaniment is provided by

a small theatre orchestra, such as might have been available in a medium-sized

theatre in a medium-sized town.

Copies of the cue sheet that accompanied

the 1927 release of Chang still exist, and this has been used as

much as possible to compile the score for tonightís screening in order

to recreate the original effect. However, certain pieces of the music

called for in the cue sheet could not be located in modern archival collections,

eight of which, particularly including the Eastman School of Music, the

University of North Texas, and the New York Public Library, are represented

in tonightís score.

One could propose that the medium-sized theatre that used a reduced orchestra

might also have had a disorganized librarian, who might not have managed

to order those selections that they didnít already own, even though the

publishers are conveniently listed in the cue sheet. In that case, the

librarian would have substituted similar music from the theatre's library.

Some substitutions have been made in this way for tonight, but these have

been supplemented by original compositions by Dr. Carli, for cues where

adequate substitutes could not be found in our own ìlibraryî of remaining

archival collections.

That service would probably not have

been provided by the orchestra conductor of a medium-sized theatre in

a medium-sized town. Fortunately, the Giornate del Cinema Muto is able

to command the services of musicians well beyond the calibre of our hypothetical

movie house, and we confidently hope that the results will be satisfying

to the audience tonight. - Alice Carli

THE FOUR FEATHERS / LE QUATTRO

PIUME (Paramount Famous Lasky Corp., US 1929)

Dir.: Merian C. Cooper, Ernest B. Schoedsack, Lothar Mendes; assoc.

prod.: David O. Selznick; sc.: Howard Estabrook; adapt.:

Hope Loring, da romanzo di /from the novel by A.E.W. Mason; didascalie/titles:

Julian Johnson, John Farrow; ph.: Robert Kurrle; 2nd unit ph.:

Ernest B. Schoedsack; mus.: William Frederick Peters; asst.

dir.: Ivan Thomas; cast: Richard Arlen, Fay Wray, Clive Brook,

William Powell, Theodore von Eltz, Noah Beery, Zack Williams, Noble Johnson;

data dist./released: 12.6.1929 (Movietone sound-on-film);

35mm, 7472 ft., 83’ (24 fps), Merian C. Cooper Papers, Harold B.

Lee Library Special Collections, Brigham Young University.

Didascalie in inglese / English intertitles.

Si tratta di una versione sorprendentemente poco avventurosa

del famoso romanzo che, nonostante la supervisione di Selznick, assomiglia

a una produzione televisiva di anni dopo, anche se arricchita dallo splendido

materiale girato in Sudan dalla seconda unità di Cooper e Schoedsack.

Era questo il terzo film muto firmato dal duo. "Avevo letto Le quattro

piume quand’ero in prigione in Russia", ha raccontato Cooper.

"Così comprammo i diritti per sette anni ed andammo in Africa;

le scene con gli ippopotami sono state girate sul fiume Rovuma, al confine

tra l’Africa Orientale Portoghese ed il Tanganika." Gli ippopotami

furono spinti in un recinto e poi contro una barricata di tronchi, aperta

ad un preciso segnale per far cadere gli animali nel fiume. La scena fu

provata 13 volte.

"A 90 miglia circa a nord di Port Sudan girammo le scene con i selvaggi.

Poi venimmo qui (in California) e facemmo costruire il forte, tra Palm

Springs ed Indio. Ingaggiammo quindi sulla Central Avenue un migliaio

di ragazzi di colore: con le parrucche erano precisi ai Fuzzy-Wuzzies.

Per quanto ne so, Schoedsack ed io abbiamo realizzato la prima carrellata

su binari. Eravamo entrambi molto ingegnosi in fatto di meccanica."

In Africa non avevano attori. Cooper funse da controfigura per Richard

Arlen, ed un assistente — o la stessa Ruth Rose (in campo lungo)

— rimpiazzò Clive Brook o William Powell. Al ritorno a Hollywood,

nelle sale trovarono The Jazz Singer (Il cantante di jazz) e Cooper,

con l’appoggio di Lasky, decise di non fare uscire il film se non

lo si rendeva sonoro. Ma Zukor decretò che era solo una moda del

momento. "Così dovetti finire questo dannato film lasciandolo

muto. Mi si spezzò il cuore."

Come supervisore fu scelto David Selznick. Grazie ad un’attenta pianificazione,

Cooper e Schoedsack poterono mettere insieme le scene nel deserto africano

e californiano ed anche le scene girate in studio senza ricorrere a nessun

tipo di immagine composita. Le scene drammatiche erano state realizzate

in fretta, e né Cooper né Schoedsack avevano esperienza

in fatto di regia di lungometraggi. "Le scene in interni non mi interessavano

granché", disse Cooper. "Ero indignato dal fatto di non

poter girare con il sonoro. Tutte le grandi scene in interni, quelle nel

forte e le scene con le piume le ho dirette io. Schoedsack non ne ha voluto

sapere."

A lavoro ultimato Schoedsack andò in Sumatra e Cooper a New York,

per contribuire alla costituzione della Pan American World Airways. Lasky

gli chiese di tornare a rigirare alcune scene. Cooper convenì che

dovessero essere rifatte e preparò dettagliate istruzioni scritte,

ma invitò lo studio a cercarsi un altro regista. Fu così

ingaggiato Lothar Mendes, che trovava eccezionale il materiale

africano, ma non le parti con gli attori. Secondo Cooper, c’erano

solo tre brevi scene da rifilmare, ma evidentemente Mendes fece molto

di più, compreso un rullo finale sonoro.

"Ritengo che David Selznick abbia sbagliato a inserire tutte quelle

didascalie e quelle scene fasulle dirette da Mendes", ha dichiarato

Cooper. "Il film, come gliel’avevamo lasciato Monte ed io, era

molto meglio."

Secondo quanto scrive Thomas Schatz in The Genius of the System (p.

78), l’anteprima di The Four Feathers fu un disastro: "Selznick

dovette fare un lavoraccio per salvare la parte avventurosa: gli toccò

rivedere la storia e organizzare il rifacimento di una serie di riprese,

senza contare la sua personale supervisione al montaggio. Il film ebbe

un moderato successo." — KB

A surprisingly unadventurous version of the famous

novel. Despite the supervision of Selznick, it has very low production

values, and resembles the sort of thing done for television years later.

It is enlivened by splendid second-unit footage shot by Cooper and Schoedsack

in the Sudan.

"The film was a mixed-up, uneven mess," said Ernest Schoedsack.

"Our patron saint, Jesse Lasky, was at the New York end of Paramount,

and we were thrown to the West Coast wolves. I was innocent of studio

politics and Coop had never seen a studio. A smart young punk named Selznick

was trying to overthrow B.P. Schulberg, and we were caught in the middle.

We had worthless, expensive writers charged to us, and many other obstructive

tactics. We had picked a young man [Charles Emmett Mack] for the part

Powell finally got, and he was killed in a car accident. Powell was superstitious

about stepping into a dead man’s shoes, and was very nasty and obstructive

throughout. Clive Brook (old mother Brook to us) hated Powell and Powell

hated Brook, and the only funny thing about the show was how they both

tried to upstage each other. Don’t blame us for the titles —

they even stole some from Kipling, with his permission!"

This was the third silent made by the team. "I’d read The

Four Feathers when I was in prison in Russia," said Cooper. "So

we bought 7-year rights on it and went to Africa, and on the Rovuma River,

which is the border between Portuguese East Africa and Tanganyika, we

shot the hippo stuff." The sequence was achieved by herding the hippos

into a corral, then crowding them against a log barricade which was opened

at a signal, cascading the hippos into the river. It had to be staged

13 times.

"We went up into the Sudan, about 90 miles north of Port Sudan, where

we shot the Fuzzy-Wuzzies. Then we came out here (to California) and built

the fort between Palm Springs and Indio and hired 1,000 dark boys from

Central Avenue and put wigs on them — they looked just the same as

the Fuzzy-Wuzzies — they charged out and hit the square. Schoedsack

and I built the first, as far as I know, travelling shot on rails. Both

of us were very inventive mechanically."

In Africa, they had no actors. Cooper doubled for Richard Arlen, and an

assistant or Ruth Rose (in long shot) would double for Clive Brook or

William Powell. When they returned to Hollywood, The Jazz Singer

was playing. Cooper decided not to go on the floor until he could shoot

in sound, and Lasky backed him up. But Zukor decided it was a passing

fad. "So I had to finish the bloody picture silent. It broke my heart."

David Selznick was appointed supervisor. Through careful planning, Cooper

and Schoedsack were able to cut together their African, California desert,

and studio scenes without resorting to any kind of composite photography.

The dramatic scenes were done in a hurry, and neither Cooper nor Schoedsack

had any experience of directing a regular feature. "I didn’t

care much about these indoor scenes," said Cooper. "I was so

disgusted at not being able to do them in sound. All the big indoor scenes,

the ones inside the fort, the feather scenes, and all that I directed

myself. Schoedsack didn’t want to direct that part."

When they finished, Schoedsack went to Sumatra and Cooper went to New

York to help form Pan American World Airways. Lasky asked him to come

back to reshoot some scenes. Cooper agreed they should be reshot, and

wrote detailed instructions, but told them to get another director. Lothar

Mendes was hired. Mendes thought the African footage was wonderful, but

he didn’t like the human element. According to Cooper, there were

only three little scenes to be reshot, but Mendes evidently did more than

that, including a final reel in sound.

"I thought David Selznick made a great mistake in putting in all

that titling and those phoney scenes directed by Mendes," Cooper

said. "It was a much better picture when Monte and I left it."

According to Thomas Schatz, in The Genius of the System (p.78),

the preview of The Four Feathers was a disaster: "Selznick

conducted a massive salvage job on the adventure drama, reconstructing

the story and setting up a programme of retakes, and then he personally

supervised the re-editing. The picture was a mild success." —

KB

RANGO / RANGO (Paramount Publix

Corp., US 1931)

Prod./Dir.: Ernest B. Schoedsack; sc.: Ernest B. Schoedsack

& Ruth Rose; ph.: Ernest B. Schoedsack; assoc. ph.:

Alfred Williams; asst. dir.: Ruth Rose; ed.: Ernest B. Schoedsack;

assoc. ed.: Julian Johnson; sd. sup.: Roy Pomeroy; mus.:

W. Franke Harling; cast: Claude King, Douglas Scott, Ali, Bin;

animali/animals: Tua, Rango; New York premiere: 18.2.1931;

16mm, 2358 ft., 65’ (24 fps), Kevin Brownlow Collection.

Prologo sonoro e narrazione in inglese. / Sound prologue and silent

film with English narration.

A parte il prologo, questo è un film sostanzialmente

muto che racconta la storia di un orangutan e che venne girato a Sumatra

da Schoedsack e Ruth Rose quando Cooper aveva abbandonato il cinema per

metter su un paio di compagnie aeree. Schoedsack si era portato dietro

lo zoom della Paramount (usato per la prima volta per It [Cosetta]

con Clara Bow). Rango è un film per bambini, ma talmente

ben girato e ricco di eventi da poter piacere anche ai loro genitori.

Gli animali e soprattutto la musica che li accompagna sono "carini"

come lo sono i documentari Disney (e, naturalmente, anche altrettanto

divertenti). Ma questo è un film ben congegnato, molto semplice

e splendidamente fotografato, con scene d’azione di grande efficacia

e trovate spassose.

Schoedsack aveva ingaggiato un cameraman, Al Williams, che però

giunse a bordo privo di sensi, trasportato da amici anch’essi sbronzi.

Una volta, durante le riprese, fu talmente spaventato da una tigre che

si prese un’altra solenne sbronza. Allora Schoedsack lo imbarcò

su una nave diretta in Europa ed effettuò lui stesso le riprese

del film.

La pellicola fu girata nelle giungle d’alta montagna della parte

nord-occidentale di Sumatra. Il governo olandese aveva concesso ai membri

della troupe il permesso di addentrarsi nella zona, declinando però

ogni responsabilità circa la loro sicurezza. C’erano infatti

problemi con la tribù Atjehnese. Schoedsack e sua moglie fecero

amicizia con gli indigeni e vissero in una capanna di bambù nei

pressi di un torrente di montagna.

Schoedsack montò il film agli Astoria Studios dove girò

il prologo. Egli lasciava sempre che fosse Cooper a tenere i rapporti

con la stampa, ma stavolta dovette sbrigarsela da solo. Il reparto pubblicità

rimase costernato sentendolo dichiarare alla stampa: "Credetemi,

non c’è stato niente di emozionante. Il film finito può

sembrare pieno di situazioni da brivido, ma girarlo è stato un

lavoro lento e tedioso, che si è protratto per otto o nove mesi.

Dovete tenere presente che il pubblico vede solo l’otto per cento

del materiale effettivamente girato. Comunque, non ho incontrato particolari

difficoltà… Il tempo era splendido…" — KB

Apart from the prologue, this story of an orang-utan

is a essentially a silent film. It was shot in Sumatra by Schoedsack and

Ruth Rose when Cooper had left the film business to organize a couple

of airlines. Schoedsack took with him Paramount’s zoom lens (first

used for the Clara Bow film It). Rango is a film for children,

but so well shot and so full of incident that it appealed to their parents

as well.

The handling of the animals, and especially the music accompanying them,

is "cute" in the same way Disney documentaries were cute (and,

of course, funny). But this is a well put-together film, very simple and

beautifully photographed, and it packs terrific punch in its frequent

bursts of action and humour.

Schoedsack took a cameraman, Al Williams, but was alarmed when he arrived

on the ship unconscious, carried by inebriated friends. Once in action,

the man became so terrified by a tiger that he drank himself senseless.

Schoedsack put him aboard a ship to Europe and photographed the film himself.

The film was made in the high mountain jungles at the northwestern end

of Sumatra. The Dutch government granted permission but refused responsibility

for the party’s safety, for the Atjehnese tribe had been giving them

trouble. The Schoedsacks befriended the natives, and lived in a bamboo

hut alongside a mountain torrent.

Schoedsack edited the film at the Astoria Studios, where he shot the prologue.

Schoedsack always left the press-agentry to Cooper, but now he was on

his own, and he dismayed the publicity department when he told newspapermen:

"Seriously, there were no thrills. The finished film may seem packed

with excitement, but making it is a long, slow, tedious business stretched

over eight or nine months. Remember, only eight percent of the stuff I

shot appears in the picture shown to the public. And, honestly, there

weren’t many difficulties... The weather was wonderful..."

— KB

CREATION (RKO, US 1932)

Prod.: Bertram Millhauser, Willis H. O’Brien, Harry O. Hoyt;

ph.: Eddie Linden, Karl Brown; adapt.: Beulah Marie Dix;

prod. artists: Mario Larrinaga, Byron L. Crabbe, Ernest Smythe,

Juan Larrinaga; technical staff: Marcel Delgado, E.B. Gibson, Orville

Goldner, Carroll Shepphird, Fred Reefe; cast: Ralf Harolde (Hallett);

frammento muto non distribuito /unreleased silent fragment, 35mm,

122m., 4’28" (24 fps), Library of Congress.

Senza didascalie / No intertitles.

Questo rullo di Creation fu rinvenuto tra gli

effetti personali di Willis H. O’Brien. Il mostro preistorico è

un triceratopo. Manca la parte finale della sequenza, quella in cui il

dinosauro trafigge Hallett con un albero uccidendolo: venne impiegata

per il montaggio preliminare di King Kong. Come per The Lost

World (Un mondo perduto; 1925), anche qui animali veri furono

usati insieme con quelli finti, ma le difficoltà create da Snooky,

una scimmia ammaestrata che aveva una sua serie con la Universal, e dal

giaguaro portarono alla decisione di girare King Kong senza animali

veri.

Willis H. O’Brien che, con il regista Harry Hoyt, aveva concepito

Creation come seguito del loro fortunatissimo The Lost World,

aveva chiamato a collaborare al suo progetto vari tecnici ed artisti,

tra cui Mario Larrinaga e Marcel Delgado, che tanto avrebbero contribuito

a King Kong. Ed è qui che lo stesso O’Brien mise a

punto gli sfondi su più piani e le combinazioni di dal vero e animazione

che avrebbero contraddistinto il film del 1933. Egli era stato autorizzato

dalla RKO a costituire una propria unità all’interno degli

studi. Creation si rivelò uno dei progetti cinematografici

più complicati mai varati. La RKO, colpita duramente dalla Depressione,

era sull’orlo della bancarotta, e nell’estate del 1931 i costi

del film erano saliti a 100.000 dollari, una somma sufficiente per cinque

produzioni a basso budget. David O. Selznick, chiamato a risollevare le

sorti della società, volle come suo vice Merian C. Cooper. Questi

rimase affascinato dal materiale girato per Creation, ma comprese

che, dopo un anno, il progetto si era arenato. La produzione fu annullata,

ma Cooper ne ricavò un sacco di idee e individuò in O’Brien

colui che avrebbe potuto dar vita al suo epico gorilla senza muoversi

dallo studio. Un rullo di prova fu realizzato per il consiglio d’amministrazione,

e fu così che King Kong sorse dalle fondamenta gettate per

Creation. — KB

This reel was found among the effects of Willis H.

O’Brien. The prehistoric monster is a Triceratops. The end of the

sequence, in which the dinosaur pushes a tree on Hallett and gores him

to death, is missing — it was borrowed for the rough cut of Kong.

As in The Lost World, live animals were used with artificial ones.

But difficulties with Snooky, a trained ape who had his own series at

Universal, and the jaguar led to King Kong being made without live

animals.

Willis H. O’Brien planned Creation with director Harry Hoyt

as a follow-up to their successful The Lost World (1925). O’Brien

brought in a number of technicians and artists, such as Mario Larrinaga

and Marcel Delgado, who would contribute so much to King Kong.

And O’Brien developed the multiplane settings and composites that

gave that picture such a fresh look. He was allowed to set up his own

unit within RKO Studios. Creation was one of the most intricately

planned film projects ever launched. RKO, hard-hit by the Depression,

was on the verge of bankruptcy, and by the summer of 1931 the costs of

Creation had reached $100,000 — five programme pictures could

be made for that. David O. Selznick was hired to rescue the company, and

he brought in Merian C. Cooper as his assistant. Cooper looked at the

material and was very impressed, but felt that after a year the project

was getting nowhere. Creation was cancelled. But it gave him ideas,

and he saw in O’Brien the man to bring his gorilla epic to life without

leaving the lot. A test reel was produced to be shown to the board of

directors. King Kong was thus built upon the foundations laid for

Creation. — KB

THE SILENT ENEMY / CARIBÙ, IL NEMICO SILENZIOSO

(Paramount, US l930)

Dir.: H.P. Carver; prod.: W. Douglas Burden, William C. Chanler;

sc.: Richard Carver; titles: Julian Johnson; ph.:

Marcel le Picard; addl. ph.: Frank M. Broda, Horace D. Ashton,

William Casel, Otto Durkoltz; asst. dir.: Earl M. Welch; technician:

L.A. Bonn; cast: Chief Yellow Robe, Chief Long Lance, Chief Akawanush,

Spotted Elk, Cheeka; sound prologue: Chief Yellow Robe; New

York premiere: 19.5.1930; 35mm, 7551 ft., 84’ (24 fps), Film

Preservation Associates.

Didascalie e prologo sonoro in inglese / Silent, with sound prologue.

English intertitles.

Negli anni ’70, Merian C. Cooper, ospite del suo

vecchio amico Douglas Burden, gli parlò del mio interesse per i

film muti, dopodiché Burden mi scrisse raccontandomi di un suo

documentario drammatico sugli Indiani d’America prima dell’arrivo

dell’uomo bianco, The Silent Enemy. Non ne avevo mai sentito

parlare ma, dato che era ispirato a Chang, cercai di procurarmene

una copia. William K. Everson mi mostrò una versione a tre rulli,

pensata per le scuole, che mi parve molto promettente. Visionai un’edizione

successiva rovinata dal commento parlato. A un certo punto la Paramount

donò all’American Film Institute i materiali da tempo dimenticati

in un magazzino: tra i 76 lungometraggi muti ivi rinvenuti c’era

— come riferì l’allora archivista dell’AFI David

Shepard — The Silent Enemy, in 9 rulli. Ripresentato nel 1973

in occasione dell’inaugurazione dell’AFI Theatre di Washington,

il film fu accolto dal pubblico con un’ovazione.

L’interprete principale, Buffalo Child Long Lance, ebbe un ruolo

di rilievo negli anni ’20 come portavoce degli Indiani d’America.

Però da recenti ricerche è emerso che si trattava un impostore:

egli era un nero della Carolina del Sud che, intuendo quella che sarebbe

stata la sua vita, riscrisse il proprio passato. Come indiano era assolutamente

convincente, e Douglas Burden, che pur doveva sapere la verità,

di certo a me non disse mai nulla.

Non fu facile mettere insieme il resto del cast. Burden girò in

lungo e in largo, dall’Alberta fino al South Dakota, selezionando

alla fine 150 indiani; era però dura trattenerli sul luogo delle

riprese, perché volevano tornare a cacciare nei loro territori.

Burden si era già fatto un nome come esploratore: era andato alla

ricerca del varano di Komodo, aveva catturato due esemplari e li aveva

portati a New York, contribuendo a ispirare il soggetto di King Kong.

Con il socio William Chanler, aveva scelto H.P. Carver come regista ed

il figlio di questi, Richard, come sceneggiatore. Carver aveva già

fatto un film sugli indiani e nutriva per essi una grande simpatia.

La trama era basata sulle Relazioni dei Gesuiti, una serie di volumi

sui viaggi dei missionari (1610-1791) vissuti nella Nuova Francia tra

gli Ojibwa (su queste stesse fonti si è basato Bruce Beresford

per Black Robe [Manto nero; 1991]). Burden, che ci teneva

all’autenticità, girò molte scene a una temperatura

glaciale, addirittura a 35 gradi sottozero. L’equivalente, in The

Silent Enemy, della carica degli elefanti di Chang è

la carica dei caribù. Per filmare gli animali Burden inviò

alle Barren Lands una spedizione capeggiata da Ilia Tolstoy (nipote dello

scrittore): "Oggi, con gli elicotteri, si sarebbe potuto riprendere

tutto quanto senza problemi, invece allora i miei uomini si dovettero

muovere in canoa. Organizzarono ottimamente i trasporti e, remando con

le pagaie, attraversarono laghi grandiosi, ma persero la migrazione. Fu

un bel danno. Dovemmo inviare in Alasca una nuova spedizione, guidata

questa volta da Earl Welch, che ha girato le immagini che vedete, facendo

un ottimo lavoro." (Burden si rammaricava che la sequenza includesse

alcune renne, che sono la versione addomesticata dei caribù.)

The Silent Enemy fu un fallimento commerciale e fu uno degli ultimi

autentici film muti presentati a Broadway. — KB

When Merian C. Cooper stayed with his old friend

Douglas Burden in the 1970s he told him of my interest in silent films,

and Burden wrote to tell me of his own drama-documentary, The Silent

Enemy, about the American Indian before the white man came. I had never

even heard of it. Since it was inspired by Chang, I tried to find

a copy. William K. Everson showed me a 3-reel version, designed for schools.

It looked very promising. A later version I saw was ruined by the narration.

Eventually, Paramount passed over to the American Film Institute a vault

they had forgotten about, and among the 76 silent features, AFI archivist

David Shepard reported, was The Silent Enemy, in 9 reels. It was

re-premiered at the opening of the AFI Theatre in Washington, DC, in 1973

and received an ovation.

The man who plays the lead in this film, Buffalo Child Long Lance, was

a prominent figure in the 1920s, a spokesman on behalf of the Indian.

But the most recent research has revealed that he was a fraud. He was

a black from South Carolina who realized what his life was going to be

like and rewrote his past. He was absolutely convincing as an Indian,

and certainly Douglas Burden, who must have known, never breathed a word

to me.

The rest of the cast was difficult to find. Burden scoured the country

from Alberta to South Dakota, finally selecting a total of 150 Indians.

It was hard to keep them on the location; they kept wanting to return

to their trapping grounds.

Burden had already won a reputation as an explorer. He had sought the

Dragon Lizard of Komodo, and had captured two and brought them to New

York, one of the events which led to King Kong. He and his partner

William Chanler selected H.P. Carver as director and his son Richard as

scriptwriter. Carver had made a film about Indians and was very fond of

them.

The story was founded on The Jesuit Relations, a series

of volumes of the travels of the missionaries in New France (1610-1791)

who lived among the Ojibwa. (This source was also the starting point for

Bruce Beresford’s 1991 film Black Robe.)

Burden put an emphasis on authenticity, and some of the scenes

were shot in extreme cold, 35 degrees below zero. The Silent Enemy’s

equivalent of the elephant stampede in Chang is the caribou stampede.

Burden sent an expedition under Ilia Tolstoy (grandson of the writer)

to the Barren Lands to capture the caribou stampede: "Today, with

helicopters, you could have filmed the whole thing without difficulty,

but then we had to send this expedition by canoe. They made terrific portages

and paddled over tremendous lakes, and missed the migration. The expedition

was a dead loss. We had to send a whole new expedition to Alaska. Earl

Welch headed that one, and he got the pictures you see. He did damned

well." (Burden was unhappy that the caribou sequence included some

reindeer, the domesticated version of the caribou.)

The film was a financial failure. And it proved to be one of the

last authentic silent films to play on Broadway. — KB

LONG LANCE / VIE ET MORT DE SYLVESTER

LONG (National Film Board of Canada, CA 1986)

Dir./researcher: Bernard Dichek; assoc. dir./prod.: Jerry D.

Krepakevich; narration written by: Donald Brittain & Bernard

Dichek; adatt. da /adapt. from Long Lance, the Story of an Imposter

di/by Donald B. Smith, e dagli scritti di /and the writings

of Long Lance; ph.: James Jeffrey; orig. mus.: Roger

Deegan; ed.: Peter Svab; exec. prod.: Tom Radford; cast:

Edmund Many Bears (Long Lance); intervistati /interviewees: Maurice

Fidler, Mrs. Sophie Allison, Iron Eyes Cody, Bessie Clapp, Domenica Pallister,

Lee Ash; narr.: Donald Brittain; estratti da / film excerpts:

The Silent Enemy (1930); video (da una copia 16mm /made from a 16mm

print), 55’, Betacam SP PAL, col., sound, National

Film Board of Canada.

Versione inglese / English dialogue and narration.

VIDEOPROIEZIONE / VIDEO PROJECTION

La straordinaria storia del capo degli indiani Piedi

Neri, rivelatosi poi un impostore, mi colpì in modo particolare

perché, in tutte le mie ricerche su The Silent Enemy, nessuno

me ne aveva mai fatto parola, nemmeno Burden. La storia è simile

a quella di Grey Owl (Gufo Grigio) portata di recente sullo schermo da

Richard Attenborough. Anche Long Lance dava importanza all’ambiente

e difendeva sui giornali i diritti degli indiani. Laddove Grey Owl veniva

da Hastings, in Inghilterra (!), Long Lance era un nero, con sangue Cherokee,

di Winston-Salem, Carolina del Nord. Da ragazzo aveva letto libri sugli

indiani ed aveva preso parte a un Wild West Show. Era poi riuscito ad

entrare a Carlisle, il college per indiani in Pennsylvania, nel periodo

in cui Jim Thorpe era il capitano della squadra di football. Scrisse al

presidente Wilson per essere ammesso a West Point, ma si fece deliberatamente

respingere agli esami. Si arruolò poi nell’esercito canadese

e fu ferito in Francia; al ritorno, iniziò a spacciarsi per un

Cherokee puro sangue. Jack Dempsey, che non avrebbe mai combattuto con

un uomo di colore, fu onorato di allenarsi con il nobile Long Lance. Egli

iniziò a visitare le tribù indiane che, pur sospettando

di lui, furono indotte a tacere dai suoi scritti appassionati sulle loro

condizioni di vita. Fu addirittura adottato dalla tribù dei Piedi

Neri, i quali lo incoraggiarono ad abbandonare il travestimento da Cherokee

per reinventarsi come loro capo, anzi, il capo. Così divenne

un eroe, un paladino della causa indiana, nonostante i suoi libri ed articoli

fossero pieni di inesattezze. La sua identità venne rivelata solo

quando partecipò a The Silent Enemy, per opera di Capo Yellow

Robe, che lo smascherò subito. Long Lance lo supplicò di

ritirare le sue accuse, Yellow Robe accettò e la Paramount poté

così proseguire con il film, che altrimenti avrebbe dovuto sospendere.

Incredibilmente, Long Lance continuò a risiedere presso l’elitario

Explorers’ Club di New York, anche quando il suo mondo era limitato

a quello dei quartieri malfamati. Morì di morte violenta nella

casa hollywoodiana della miliardaria Anita Baldwin.

Considerato il trattamento riservato ai nativi americani, è curioso

notare quante persone si siano finte indiane. Anche i produttori di quest’affascinante

documentario sono stati caduti nella trappola di un impostore. Solo dopo

la sua morte, si è saputo che Iron Eyes Cody, il celebre attore

e consulente indiano, era un siciliano senza una sola goccia di sangue

pellerossa ma con una bella faccia tosta. Le scene ricostruite sono molto

sobrie, ed Edmund Many Bears è superbo nei panni di Long Lance.

È però tragico pensare che un uomo brillante e pieno di

talento come Long Lance avrebbe potuto diventare un affermato attore holywodiano,

mentre invece il segreto del suo passato lo ha tormentato fino a distruggerlo.

— KB

The extraordinary story of the chief of all the Blackfoot

Indians, who turned out to be an imposter, astounded me because in all

my researches into The Silent Enemy no one — not even Douglas

Burden — breathed a word. The story bears comparison with that of

Grey Owl, recently filmed by Richard Attenborough. Long Lance was also

concerned about the environment and championed Indian rights in the newspapers.

Whereas Grey Owl came from Hastings, England(!), Long Lance was a black

man with Cherokee blood from Winston-Salem, NC. As a boy, he read books

about Indians and joined a Wild West show. He managed to get into Carlisle,

the Indian college in Pennsylvania, when Jim Thorpe led the football team.

He wrote to President Wilson and was accepted into West Point, but deliberately

failed the exams. He joined the Canadian army and was wounded in France.

When he returned, he posed as a full-blooded Cherokee. Jack Dempsey, who

would never fight a coloured man, was happy to spar with the noble Long

Lance. He began to visit Indian tribes, and although they were suspicious

of him, his passionate writings about their conditions persuaded them

to keep quiet. He was even adopted into the Blackfoot tribe, which encouraged

him to shed his disguise as a Cherokee and to reinvent himself as a chief

of the Blackfoot, and eventually the Chief. He became a hero, a

champion of Indian causes, even though his books and articles were full

of inaccuracies. It was not until he made The Silent Enemy that

his identity was revealed — by Chief Yellow Robe, who knew at once

that he was not what he claimed to be. Long Lance pleaded with him;Yellow

Robe withdrew his charges, and Paramount carried on with a release which

they would otherwise have had to cancel. Incredibly, Long Lance continued

to live at the elite Explorers’ Club in New York, even when his world

was reduced to that of Skid Row. He came to a violent end at the Hollywood

home of millionairess Anita Baldwin.

Considering how Native Americans have been treated, it is curious

how many people have pretended to be Indian. The producers of this fascinating

film fell for an imposter themselves. Iron Eyes Cody, the celebrated Indian

actor and adviser, was revealed after his death to have been a Sicilian,

with no Indian blood, but lots of chutzpah. The re-enactments are soberly

done, and Edmund Many Bears looks superb as Long Lance. What is so tragic

is that Long Lance was obviously a brilliantly talented man, who might

have become a successful actor in Hollywood, but the secret of his past