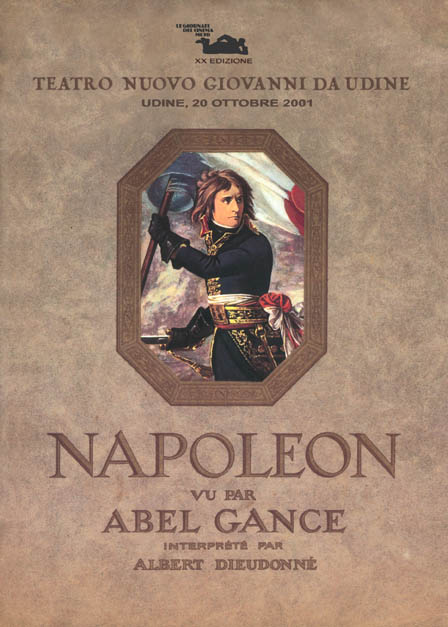

NAPOLEON vu par ABEL GANCE

The BFI Collections restoration of NAPOLEON

presented in association with Photoplay Productions

Udine, Teatro Nuovo Giovanni da Udine, 20.10.2001

NAPOLÉON VU PAR ABEL GANCE / NAPOLEON / NAPOLEONE (Consortium

Westi/(Ciné-France-Films)/ Films Wengeroff/Pathé Consortium/Films

Abel Gance (1925), Societé Générale de Film (1926),

F 1927)

Dir.: Abel Gance; asst. dirs.: Henry Krauss, Vladimir Tourjansky,

Henri Andréani, Alexandre Volkoff, Marius Nalpas, Pierre Danis;

Dir. of Ph.: Jules Kruger; chief cameraman: Joseph-Louis

Mundviller; additional ph.: Léonce-Henry Burel; ed. associates:

Marguerite Beaugé, Henriette Pinson (negative); art dir.:

Alexandre Benois, Pierre Schildknecht, Alexandre Lochakoff, Georges Jacouty,

Vladimir Meinhardt; technical specialists: Michel Feldman, Simon

Feldman, Maurice Dalotel, W. Percy Day, Edward Scholl; spec. effects.:

Nicolas Wilcke, Paul Minine, Segundo de Chomon; costumes: Charmy,

Alphonse Sauvageau, Mme Augris, Mme Neminsky; Mme. Manès’

costumes: Jeanne Lanvin; costume supplier: Muelle & Souplet;

footwear: Galvin; wigs: Pontet-Vivant; make-up: Vladimir

Kwanine, Boris de Fast; explosives: Ruggieri; weapons: Lemirt;

stagiaires/trainee assistants: Jean Mitry, Jean Arroy, Sacher Purnal,

Blaise Cendrars; cast: Albert Dieudonné (Napoleon Bonaparte),

Vladimir Roudenko (Napoleon Bonaparte as a boy), Nicolas Koline

(Tristan Fleuri), Petit Roblin (Picot de Peccaduc), Petit Vidal (Phélippeaux),

Robert Vidalin (Camille Desmoulins), Francine Mussey (Lucille Desmoulins),

Harry Krimer (Rouget de Lisle), Alexandre Koubitsky (Danton), Antonin

Artaud (Marat), Edmond Van Daële (Maximillian Robespierre), Maryse

Damia (La Marseillaise), Gina Manès (Joséphine de Beauharnais),

Max Maxudian (Barras), Andrée Standard (Thérèse Cabarrus

[Mme. Tallien]), Suzy Vernon (Mme. Récamier), Carrie Carvalho (Mademoiselle

Lenormond), Louis Sance (Louis XVI), Suzanne Bianchetti (Marie Antoinette),

Yvette Dieudonné (Elisa Bonaparte), Eugénie Buffet (Lætitia

Bonaparte), Georges Lampin (Joseph Bonaparte), Sylvio Cavicchia (Lucien

Bonaparte), Henri Baudin (Santo-Ricci), Acho Chakatouny (Pozzo di Borgo),

Maurice Schutz (Pascale Paoli), Marguerite Gance (Charlotte Corday), Annabella

(Violine Fleuri), Serge Freddy-Karll (Marcellin Fleuri), Léon Courtois

(Général Carteaux), Philippe Hériat (Salicetti),

Adrien Caillard (Thomas Gasparin), Alexandre Bernard (Général

Dugommier), Gilbert Dacheux (Général du Teil), Jean Henry

(Sergent Junot), Pierre Danis (Muiron), Jack Rye (Général

O’Hara), Henry Krauss (Moustache), Pierre De Canolle (Capitaine August

Marmont), W. Percy Day (Admiral Hood), Abel Gance (Louis Saint-Just),

François Viguier (Couthon), Janine Pen (Hortense de Beauharnais),

Georges Hénin (Eugène de Beauharnais), Pierre Batcheff (Général

Lazare Hoche), G. Cahuzac (Vicomte de Beauharnais), Jean d’Yd (La

Bussière), Jean Gaudray (Jean Lambert Tallien), Alexandre Mathillon

(Général Schérer), Mme. Blanche Baume (Marat’s

servant), Dancers from the Casino de Paris, Apollo, Moulin

Rouge, Folies-Bergère (dancing girls); orig. distrib:

Gaumont-Metro-Goldwyn; première: 7.4.1927, Théâtre

National de l’Opéra, Paris; 35mm, 24,745ft., 333’ (plus

3 intervals) (20 fps; except first 2 rls. [episode 1,

Brienne], 18 fps), imbibizioni e viraggi / tinted and toned, BFI

Collections (National Film and Television Archive). Didascalie in inglese

/ English intertitles.

Musica composta e arrangiata da / Music composed and arranged by

Carl Davis,

esegue / performed by Camerata Labacensis, Ljubljana, dirige /

conducted by Carl Davis.

Orchestrazioni aggiuntive di / Additional orchestrations by

Colin Matthews, David Matthews, Christopher Palmer, Nic Raine.

Kevin Brownlow e Napoléon

Il mio primo incontro con il film risale a quando andavo a scuola.

Vidi due rulli di pellicola con il mio proiettore amatoriale a 9,5 e rimasi

affascinato dal suo senso cinematografico: non avevo mai visto niente

di simile e mi ripromisi di trovare altro materiale del film e sul film.

Mi lasciava perplesso l’antipatia suscitata dal film tra i critici

e gli storici che ricordavano l’edizione originale, per cui, ad ogni

sequenza che riscoprivo, mi aspettavo di dover ammettere che avevano ragione

loro e di trovarmi di fronte a un crollo improvviso della qualità.

Ma più materiale nuovo trovavo e più il film diventava bello.

Solo più tardi scoprii che la maggior parte di quei critici aveva

visto solo versioni massacrate dai tagli.

Quando divenni montatore iniziai a guadagnare abbastanza per fare un buon

restauro. Il National Film Archive, che in seguito adottò il progetto,

mi fornì tutta l’apparecchiatura necessaria. Ogni volta che

al National Film Theatre venivano proiettate le parti di pellicola man

mano restaurate, la sala era gremita di persone che reagivano con entusiasmo.

Nel 1979 al Festival di Telluride nel Colorado gli spettatori rimasero

svegli un’intera notte per vederlo, nonostante la proiezione fosse

all’aperto a temperature glaciali. In quell’occasione anche

Abel Gance, allora novantenne, vide il film dalla finestra della sua camera

d’albergo.

L’apice venne toccato nel 1980 quando, per cconto della Thames Television

e del British Film Institute, David Gill ed io organizzammo, all’Empire

Theatre di Leicester Square a Londra, la prima proiezione con l’orchestra

dal vivo. Carl Davis compose la monumentale partitura in tre mesi e diresse

la Wren Orchestra. Prima dello spettacolo eravamo tutti nervosissimi.

Che diritto avevamo di aspettarci che il pubblico rimanesse seduto per

ben cinque ore a guardare un vecchio film muto? E in effetti il pubblico

non restò seduto; si alzò in piedi ed esplose in un applauso

senza fine. È stato il momento più commovente che abbia

mai vissuto in un cinematografo.

(Kevin Brownlow, introduzione a Napoléon as Seen by Abel Gance,

a cura di Bambi Ballard, Faber and Faber, 1990.)

Questo è il terzo restauro completo di Napoléon.

Sulla base della versione del 1980, Bambi Ballard ha prodotto una versione

ampliata utilizzando tutto il materiale della Cinémathèque

française che era stato portato al National Film and Television

Archive e qui duplicato da João Oliveira. Nel 1999, grazie al supporto

finanziario di Erik Anker-Petersen, fu iniziato un nuovo restauro presentato

per la prima volta alla Royal Festival Hall in occasione del 56°

Congresso Annuale della International Federation of Film Archives (FIAF),

tenutosi a Londra nel giugno 2000.

Il materiale importato dalla Francia è stato duplicato e inserito

nella copia di lavorazione. La differenza è enorme rispetto al

precedente restauro: le nuove parti di pellicola sono di alta qualità

e le nuove didascalie facilitano la comprensione della narrazione e rendono

la storia più interessante.

Le didascalie del vecchio restauro erano state con poca spesa non avevano

niente a che vedere con i caratteri in grassetto in stile XVIII secolo

utilizzati nella versione originale. Abbiamo filmato di nuovo (e tradotto

di nuovo) tutte le didascalie nei caratteri originali — il tondo

per le descrizioni e il corsivo per i dialoghi —, il che dà

al film tutta un’altra aria. Abbiamo trovato sia i titoli originali

sia gran parte dei credits e siamo quindi in grado di riprodurli esattamente.

Abbiamo deciso di mantenere il titolo francese Napoléon vu par

Abel Gance, perché è difficile tradurlo.

Il primo episodio — Napoleone ai tempi della scuola a Brienne —

fu ripreso da un cameraman diverso da quello che lavorò al resto

del film e molti si sono lamentati che la velocità di proiezione

era eccessiva. Per questo motivo ora proiettiamo "Brienne" a

18 fotogrammi al secondo con la musica sincronizzata a questa velocità

e il resto del film a 20 fotogrammi al secondo.

Quando abbiamo trovato materiale di qualità migliore per la stessa

scena l’abbiamo utilizzato; in alcuni casi abbiamo trovato scene

superiori a livello fotografico, ma con una recitazione più scadente

e le abbiamo pertanto scartate. Ad esempio, nell’episodio di Tolone,

si vede Napoleone scendere da cavallo due volte — un errore di montaggio

di un assistente che stava cercando di fare un altro negativo. In questo

caso abbiamo optato per la scena migliore, quella in cui Napoleone scende

da cavallo una volta sola con piglio professionale, anche se la pellicola

è rovinata nell’area poi occupata dalla colonna sonora. Nella

scena del matrimonio, il materiale nuovo è di qualità molto

migliore e quindi lo abbiamo utilizzato per la prima metà, ma la

recitazione di Dieudonné non è altrettanto buona nella seconda

parte della sequenza e così siamo ritornati all’originale,

nonostante i segni di decomposizione.

Alcune sequenze, ad esempio quella della Marsigliese, sono state

completamente sostituite perché i rulli di pellicola ritrovati

sono chiaramente quelli definitivi. Questi rulli indicavano anche dove

doveva iniziare e finire l’imbibizione e fornivano dei campioni,

cui ci siamo rigorosamente attenuti.

Certi pezzi nuovi non si prestavano proprio ad essere inseriti. Come si

può utilizzare la scena della gendarmerie che dà

la caccia a Napoleone fra i monti all’inizio della sequenza dell’inseguimento

in Corsica, quando nella scena che abbiamo si vedono uomini a cavallo

su un terreno completamente diverso? Nella scena della "doppia tempesta"

è curioso come il nuovo negativo sia esattamente uguale a quello

vecchio, inquadratura dopo inquadratura, tuttavia con alcuni fotogrammi

di differenza.

La prima volta che restaurai il film mi ritenevo fortunato quando trovavo

pellicola in più, ma questa volta mi sono spesso ritrovato con

tre versioni della stessa scena, ciascuna con piccole differenze nella

recitazione o nella regia rispetto alle altre. Talvolta erano le scene

stesse a decidere per me. Mme. Tallien arriva al Bal des Victimes e se

ne sta lì in piedi, tutta elegante. In un’altra versione,

probabilmente un rifacimento, Mme. Tallien arriva e viene accolta da una

pioggia di petali di rosa. In certi casi la recitazione era migliore,

ma non l’angolazione della macchina da presa o viceversa. È

stato perciò enormemente difficile scegliere cosa utilizzare. La

scena che mi ha messo a più dura prova è stata quella della

"morte di Marat", una scena completamente nuova e lunga il doppio

rispetto alla vecchia. Dapprima decisi di tenerla, ma quando la proiettammo

ci accorgemmo che qualcosa non andava nel trucco di Marat — ovviamente

anche Gance aveva tagliato la scena per la stessa ragione. In uno o due

altri punti, Gance aveva fatto dei tagli invece di aggiunte e io ho generalmente

seguito le sue scelte. Talvolta è stato necessario utilizzare una

scena extra senza grande valore allo scopo di spiegare una bellissima

scena successiva, come nel caso di Joséphine che suona l’arpa:

essa è seguita da una deliziosa scena della figlia che parla con

il proprio pappagallo della madre e di Napoleone.

Kevin Brownlow and Napoleon

I first encountered the film when I was a schoolboy. I saw two reels

on my 9.5mm home movie projector. I was stunned by the cinematic flair

— I had never seen anything comparable — and I set out to

find more of it, and more about it. I was puzzled by the antipathy the

film aroused among critics and historians who remembered the original

release. I expected with each rediscovered sequence that they would

be proved right, and the quality would take a plunge. But the more I

added to the film, the better it became. And eventually I discovered

that most of those writers had seen one of the butchered versions.

When I became a feature-film editor, I began to earn enough to do a

proper restoration. I was given facilities by the National Film Archive

(who eventually took the project over). Whenever the work-in-progress

was screened at the National Film Theatre, the place was always packed,

the reaction always very strong. People stayed up all night to watch

it at the Telluride Film Festival, Colorado, in 1979, even though it

was projected outdoors in freezing temperatures. Watching from his hotel

window was Abel Gance himself, then in his ninetieth year.

The climax came in 1980, when David Gill and I staged the first performance

with live orchestra for Thames Television and the British Film Institute

at the Empire Theatre, Leicester Square, London. Carl Davis created

the massive score in three months and he conducted the Wren Orchestra.

We were all intensely nervous before the show. What right had we to

expect the public to sit still for an old silent film lasting five hours?

Of course, they did not sit still. They rose to their feet and gave

it a standing ovation. It was the most moving occasion I have ever attended

in the cinema.

(Extract from Kevin Brownlow’s introduction to Napoléon

– Abel Gance, edited by Bambi Ballard (Faber and Faber, 1990)

This is the third full-scale restoration of Napoleon.

Based on the 1980 version, an extended version was produced by Bambi Ballard

using all the material held by the Cinémathèque Française.

This extra material was brought over to the National Film and Television

Archive and copied by João Oliveira. Thanks to the financial support

of Erik Anker-Petersen, a new restoration was begun in l999. This latest

restoration was first shown at the Royal Festival Hall as the gala opening

of the 56th Annual Congress of the International Federation of Film Archives

(FIAF) in London in June 2000.

The material imported from France has been copied and cut into

the cutting copy. It makes a difference — the additional footage

is of high quality and with the additional titles makes the narrative

easier to follow, and more interesting.

The titles for the old restoration were made very cheaply, and

had no connection with the bold l8th-century typefaces used in the original.

We have reshot (and retranslated) all the titles using the original typefaces

— Roman for descriptive and italic for dialogue — and this makes

a considerable difference to the look of the film. We have found the original

main titles and most of the credits, and can reproduce these exactly.

We are sticking to the French title Napoléon vu par Abel Gance,

as it is difficult to translate.

The first episode — Napoleon’s schooldays in Brienne —

was photographed by a different cameraman from the rest of the film, and

several people complained that we were running it slightly too fast. So

we are now projecting Brienne at 18 fps, and the music has been adjusted

accordingly. (The remainder goes at 20fps.)

Where we have found better quality material for the identical scene,

we have used it — but in some cases we have found scenes of superior

photographic quality, but the performance is inferior. These have not

been used. For instance, in the Toulon section, Napoleon is seen dismounting

from his horse twice — a bad piece of editing by an assistant trying

to make up yet another negative. We have remained with the better scene

— in which he dismounts once, very professionally — even though

it is marred by having the soundtrack area blanked out. In the wedding,

the new material is of much better quality, and we have used it for the

first half — but Dieudonné’s performance is not as good

in the latter half of the sequence, and we have returned to the original,

despite the signs of decomposition.

There are some substitutions of complete sequences — such

as the Marseillaise — because the reels discovered are clearly definitive.

These reels also indicated where tinting should start and end, and provided

samples so we can reproduce these exactly.

Some of the new material simply did not fit. How can you use the

Corsican gendarmerie chasing Napoleon uphill at the opening of

the chase across Corsica sequence, when the opening we have shows the

horsemen in completely different terrain? In the Double Storm, it is odd

how the new negative matches the old one shot for shot, yet with each

one differing by a few frames.

The first time I did the restoration, I felt lucky to find anything extra.

This time I often had three versions of the same scene, but played or

directed in a slightly different way. Sometimes, the decision was made

for me. Mme. Tallien arrives at the Bal des Victimes and simply stands

there, looking elegant. In another — probably reshot — version,

Mme. Tallien arrives and is showered with rose petals. Sometimes the playing

was better, but the camera angle slightly inferior, or vice versa. I therefore

had enormous difficulty in deciding which to use. The most taxing of these

sequences was a brand-new "Death of Marat" sequence — twice

as long as the old one. I decided to go with this new one, but when we

projected it we realised there was something seriously wrong with the

makeup on Marat, which obviously had caused Gance to cut it down himself.

In one or two other places, Gance had made cuts rather than additions,

and I generally followed him. Sometimes it was necessary to use an extra

scene of no particular merit in order to explain the excellent scene that

follows — as with Josephine playing the harpsichord, which is followed

by a delightful scene of her daughter talking to her pet parrot about

her mother and Napoleon.